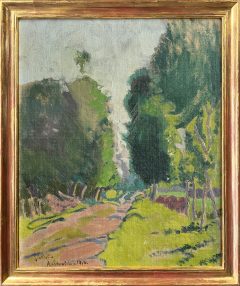

Walter Richard Sickert RA (1860 - 1942)

Showing all 2 results

Sickert

Walter Richard Sickert RA (1860 – 1942)

Walter Sickert was a key figure establishing a specifically British modernism. He was an innovative painter, draughtsman, printmaker and teacher. Becoming a Royal Academician in 1934 but resigned the following year after falling out with the President.

Born into an artistic family in Germany, Sickert moved to England aged eight. In London, he briefly attended the Slade School of Fine Art before abandoning formal studies to train under James McNeill Whistler. This exposed the young Sickert to novel techniques, shaping his loose painting style. Through Whistler, Sickert met Edgar Degas, forging an incredibly formative relationship. Degas encouraged Sickert to tackle a wide range of subject matter, portraying urban scenes in Paris and Dieppe, including forms of entertainment such as music-halls and the circus. In 1888, Sickert joined the New English Art Club (NEAC) marking his coming-of-age as an artist and stepping out of the shadows of his mentors.

Time spent in France and Venice in the 1890s provided Sickert with plentiful inspiration, and he painted cityscapes and architecture with bold brushstrokes. He also experimented with figure-painting while in Venice, having found little success as a portrait painter in London. These intimate depictions, with Venetian prostitutes posing in a simple domestic interior, were the first forays into painting scenes of social reality for which Sickert is best-known.

Camden Town

In 1905 Sickert returned to London, moving to Camden Town. The grey urban light and social deprivation of the city made for fitting new subjects for Sickert’s brush. He founded the Camden Town Group in 1911 to promote works by local artists. The paintings Sickert produced during this time were among his most socially-charged, presenting honest representations of the economic and emotional hardships of Londoners’ daily life.

During the First World War, Sickert spent much of his time teaching. In the following years, he returned to France and resumed painting scenes in and around Dieppe. Throughout the 1920s he concentrated on portrait-painting. Aided by the new technology of photography. This allowed him to find subjects without the physical presence of a sitter. Elected Associate Royal Academician in 1924. He exhibited at every Summer Exhibition from 1927 to 1935, submitting characterful portraits that prompted much critical and public debate.

Royal Academy

Sickert was elected full Academician in 1934. and offered his painting Fabia Drake as Lady Macbeth (1933, now in a Private Collection) as his Diploma Work. This painting was refused, however, on the grounds that it was not truly representative of his artistic output. Instead, Sickert donated Santa Maria della Salute, Venice (c. 1901), showing the grand Venetian church in muted tones with thickly layered paint. This work in the RA Collection exhibits Sickert’s mastery of interweaving subject matter and technique, evoking the ornate three-dimensionality of the Baroque building through heavy, almost sculptural use of paint.

Sickert’s membership of the Royal Academy was short-lived. Following the President William Llewellyn RA’s decision in 1935 not to support the preservation of Jacob Epstein’s public sculptural reliefs on the Strand, Sickert resigned in outrage.

In the last decade of his life Sickert mostly painted rural landscapes. His ailing health causing him to require assistance with completing the works. He moved to Bathampton in 1938 and continued to paint until his death in 1942.

The twenty-first century has seen a sustained period of Walter Richard Sickert research and exhibitions. Crystallising his reputation as one of the most significant British artists of the early modern period. In addition, his celebrity was assured by the crime fiction writer, Patricia Cornwell. Who published a book claiming that Sickert was Jack the Ripper. Her assertions caused a schism among Sickert scholars. But were widely agreed to be improbable and unsubstantiated. The arguments she propounded in Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed were systematically countered by Matthew Sturgis in the last chapter of his extensive biography. Walter Sickert: A Life, published in 2005.

There are hundreds of examples of Sickert’s work in public collections around the world.